Storm Éowyn hit the west coast of Ireland in the early hours of 24 January 2025. According to Met Éireann, the storm (based on preliminary evaluation) broke the land records for Ireland of 10‑minute surface mean wind speed (142 km/h, 39.4 m/s) and wind gusts (184 km/h, 51.1 m/s) at the coastal station at Mace Head, County Galway. The storm caused widespread disruption in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland and also affected Scotland later on. Ahead of the storm, Met Éireann issued red warnings for the whole country, and the UK Met Office did the same for Northern Ireland and parts of Scotland. 768,000 customers were without power in the Republic of Ireland, with nearly 326,000 customers affected in Northern Ireland. Estimates suggest that twice as many trees fell during the storm as there would normally be felled in a year. Here we present forecasts of the event provided by ECMWF’s Integrated Forecasting System (IFS) and Artificial Intelligence Forecasting System (AIFS).

Meteorological situation

The cyclone formed over the western Atlantic on 22 January. It quickly moved across the Atlantic on 23 January and rapidly intensified under an extremely strong jet stream (>100 m/s at 250 hPa in ECMWF’s analysis). The lowest measured pressure (940 hPa) was on the station Belmullet at 03–04 UTC on 24 January, and the 06 UTC analysis from ECMWF had a minimum pressure off the coast of 941 hPa. Satellite images suggest that the most extreme wind was likely due to a sting jet feature southwest of the storm centre.

ECMWF’s forecasts

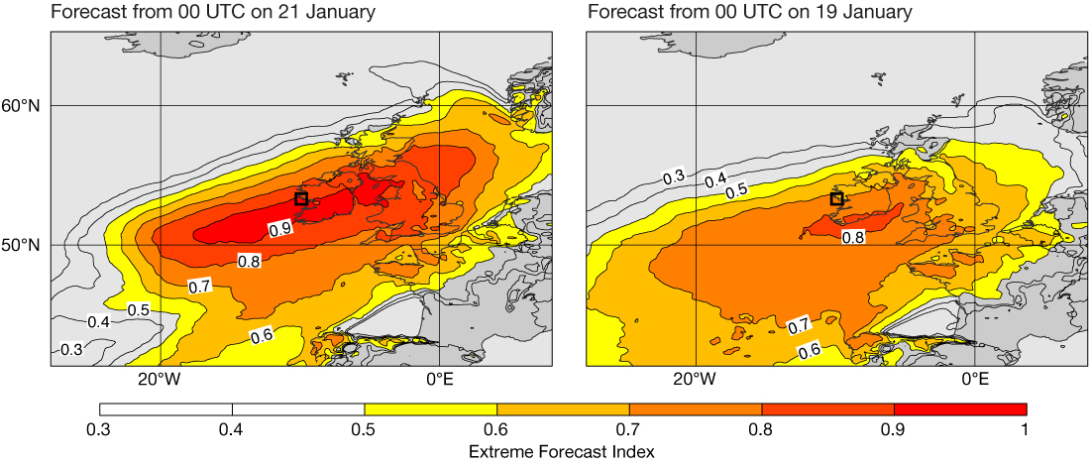

The signal for the event started to develop in ECMWF ensemble forecasts (IFS-ENS) from 18 January, about six days before the event. The examples of the Extreme Forecast Index (EFI) for 24‑hour maximum wind gusts on 24 January included here are from 00 UTC on 19 and 21 January (see the figure). In the forecast from 19 January, the centre of the highest EFI was to the south of where the highest wind speeds were recorded (black square symbol), but the forecast still provided an early warning for most of the island. In the forecast from 00 UTC on 21 January, large parts of Ireland had an EFI of about 0.9. For Mace Head (black square), 50% of the ensemble members predicted maximum wind gusts higher than the maximum in the model climate for this time of the year (not shown).

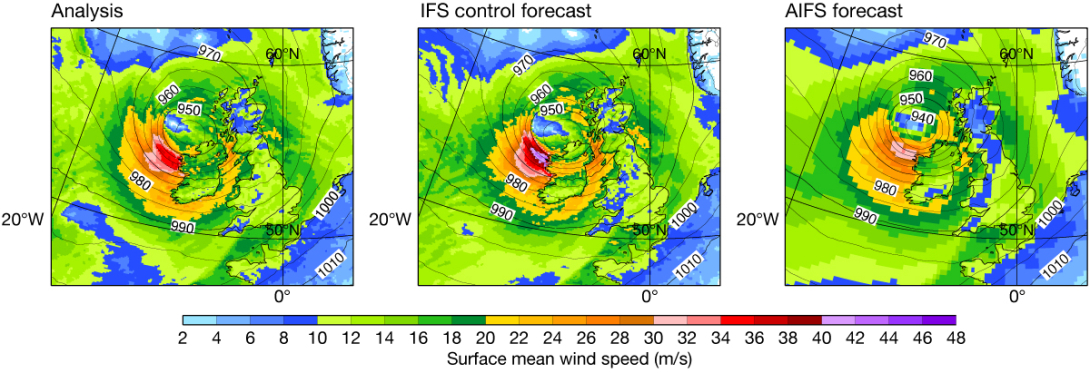

The plots in the second figure show the mean sea level pressure and the surface mean wind speed valid at 06 UTC on 24 January in the ECMWF analysis and in 30‑hour forecasts (initialised at 00 UTC on 23 January). The forecasts are the IFS control forecast (IFS-CF) and the AIFS Single v1.0, which was pre-operational at the time. Both forecasts captured the position of the storm very well at this stage. For the minimum pressure, the AIFS predicted an even deeper cyclone (935 hPa) than the IFS control forecast (940 hPa). However, at the same time the maximum mean wind speed was considerably lower in the AIFS than in the IFS control forecast (30 m/s vs. 44 m/s). The analysis provided a wind speed of 38 m/s. As the maximum wind speed is believed to be in the narrow region of the sting jet, it is very difficult to verify the maximum wind speed over the sea as we only have a few buoy measurements, and none of the available buoys were located near the extreme.

To look further into the prediction of maximum mean wind at Mace Head, the third figure shows the ensemble forecast from 00 UTC on 23 January, using hourly output. The plot also includes hourly (not maximum) 10‑minute mean wind from SYNOP weather station observations. The IFS-ENS control and many members provided a peak in the wind speed with similar magnitude and timing as the observations. However, a few ensemble members predicted very extreme mean wind speed, with the most extreme one reaching above 50 m/s. While it is not possible to verify if this was a potential scenario for a single case, the predicted value was more than 10 m/s above the observation, which is now a preliminary record for the Republic of Ireland.

The feedback from Met Éireann was that the IFS performed in general well with the structure of the system, as well as performing well on a number of parameters, including mean winds for the storm, predicting hurricane force 12 mean wind speeds in the vicinity of Mace Head. Predicted gusts were also well forecast in terms of spatial distribution and peak amplitude gusts, while the rainfall was too low. Some ensemble members with extreme wind values would generally have been discounted as outliers. A good consistency in the runs with regard to track and depth of the predicted low led to good confidence in the forecast room, leading to high-level warnings issued relatively early on.

Outlook

In summary, the ECMWF forecasts gave an early warning for the storm around 5–6 days in advance. The AIFS captured the pressure of the storm very well but underestimated the maximum wind speed. Future evaluation will also include the new AIFS ensemble that is under development. This result is in line with previously evaluated windstorms. For the IFS ensemble, we identified a few members with very extreme wind speed. After the implementation of IFS Cycle 49r1 in November 2024, we became aware of occasional ensemble members giving very high mean wind speeds during windy days. This triggered a deeper analysis of the ensemble statistics and further experimentation. It was identified that perturbations related to the surface momentum flux in the new Stochastically Perturbed Parametrizations (SPP) model uncertainty scheme played a major role in the members with extreme wind speed. While it is difficult to verify the reliability of forecasts for the most extreme winds, we are considering ways to address this issue in IFS Cycle 50r1 planned for implementation later this year (see ECMWF’s ‘Known IFS forecasting issues' page for more details: https://confluence.ecmwf.int/display/FCST/Known+IFS+forecasting+issues).