Credit: ESA/ATG medialab

Launched in May 2024, the EarthCARE satellite’s unique combination of instruments – a radar, a lidar, an imager and a broadband radiometer – will improve the modelling of clouds, aerosols and precipitation in a number of different ways.

A key novelty of EarthCARE is the potential to use the synergy of the four instruments to infer the properties of clouds and how they interact with solar and thermal-infrared radiation.

From this, we can evaluate and improve how cloud processes are represented in weather and climate models. Changes in clouds are a key source of uncertainty in climate projections and have been implicated in the surge in global temperature in 2023.

An aspect not covered in this article is that we are also working on assimilating the new radar and lidar data into our operational system. This is done to improve the analysis of current weather conditions, which serves as the starting point for weather forecasts.

New measurements

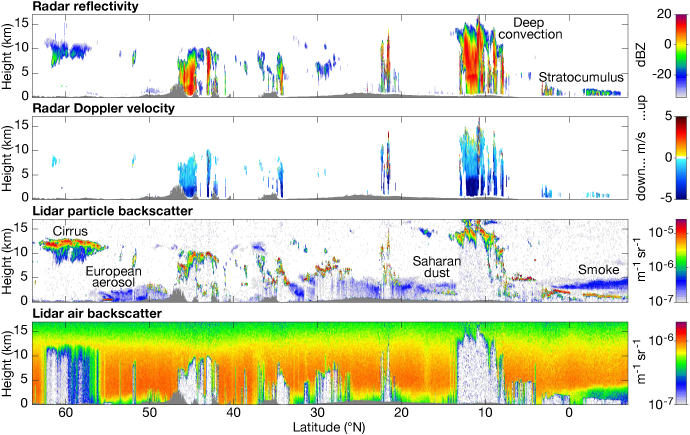

The European Space Agency (ESA) has illustrated the synergy aspects of EarthCARE using observations from 18 September 2024. The figure below shows radar and lidar observations from the same case. A multitude of atmospheric phenomena can be identified including various types of cloud, precipitation and aerosol.

The EarthCARE radar and lidar observations from 13:45 to 14:05 UTC on 18 September 2024 between Sweden (left) and the Gulf of Guinea (right).

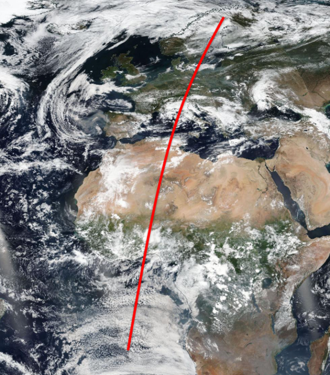

The following image traces the path along which the observations were made, on satellite images from the same time.

EarthCARE track from the case shown above, superimposed on a composite of geostationary satellite images.

Particularly novel aspects of EarthCARE are the radar’s Doppler velocity measurements and the ‘high spectral resolution’ capability of the lidar.

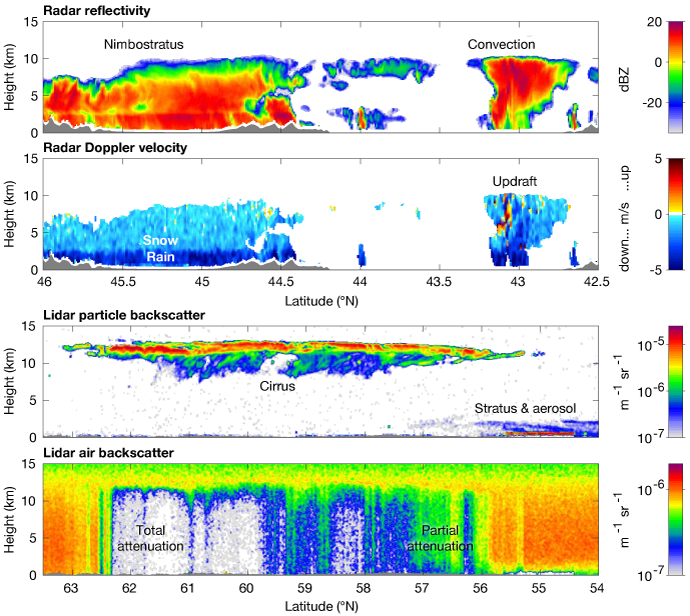

The top two panels of the figure below zoom into raining clouds over Italy and the Mediterranean. “The sharp increase in fall speed when the snow melts to form rain is clearly visible, and we are already using this to evaluate the fall speeds of snow and rain in the ECMWF model,” says Robin Hogan, an ECMWF scientist working on the application of EarthCARE data.

Especially exciting is the capability to measure the strength and width of updrafts in the cores of thunderstorms, shown in the cloud at 43°N. This will be of great interest for evaluating the structure of storms in km-scale and cloud-resolving models.

Zooming in to particular features from the first figure of EarthCARE radar and lidar observations: the top two panels show radar observations of raining clouds between the Swiss Alps (left) and Corsica (right), while the bottom two panels show lidar observations of a cirrus cloud over Sweden.

The high spectral resolution capability of the lidar enables it to separately measure how much of the reflection is from cloud and aerosol particles, and how much is from air molecules. The bottom panel of the figure above shows the reflection from air molecules in the vicinity of an extensive cirrus cloud. It shows very clearly where and by how much the light from the lidar has been blocked by the cloud above. This enables the optical properties of clouds and aerosols to be estimated more precisely than has been possible from space before.

Combining the data

ECMWF scientists are responsible for the development of EarthCARE’s official ACM-CAP algorithm, building on work started at the University of Reading, UK. This combines the data from the radar, lidar and imager to obtain a ‘best estimate’ of the properties of clouds, aerosols and precipitation beneath the satellite.

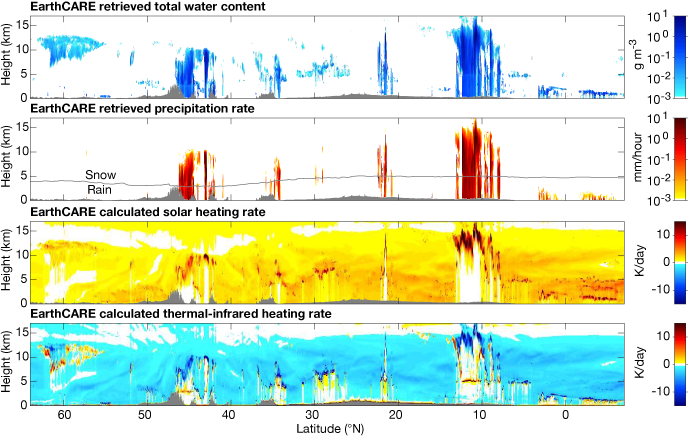

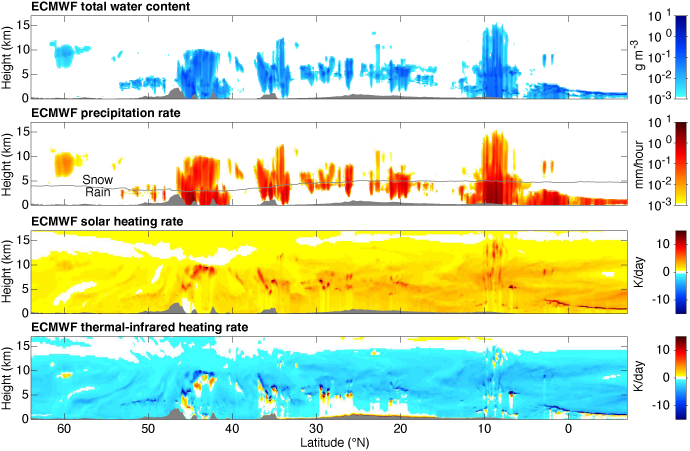

It relies on earlier processing of the individual radar and lidar data by algorithms developed at McGill University, Canada, and the Dutch national meteorological service (KNMI), respectively. The figure below depicts the cloud water content (liquid and ice) and the rain and snow rates estimated by ACM-CAP for the case shown in the first figure of EarthCARE radar and lidar observations.

Atmospheric properties estimated from EarthCARE observations. The line on the second panel indicates the 0°C isotherm separating snow from rain, above which the ‘melted-equivalent’ snowfall rate is shown in mm/hour.

In the final stage of the EarthCARE processing, the retrieved cloud and aerosol properties (such as mass and particle size) are passed to a radiative transfer code developed at Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). This code computes the solar and thermal-infrared radiation fluxes and atmospheric heating rates.

The figure above also shows the solar and thermal-infrared heating rates for this case. It can be seen that the sun strongly heats the tops of clouds, particularly the large storm cloud over Benin at around 11°N. This is partly compensated by cooling (negative heating rates) through the emission of thermal radiation to space, although thermal radiation can also heat the base of clouds.

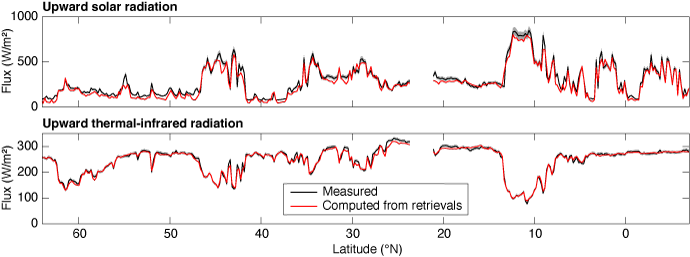

But are the retrieved cloud properties and corresponding radiative heating rates accurate? A unique aspect of the design of the EarthCARE mission is that part of the operational processing consists in performing an independent evaluation of these estimates. To demonstrate this, the figure below compares the upward solar and thermal-infrared fluxes measured directly by EarthCARE’s broadband radiometer (processed by algorithms developed at the Royal Meteorological Institute of Belgium) with those computed using the radiation code.

In the thermal-infrared, the agreement is excellent, with a root-mean-squared difference of only 8 W m-2. The agreement in the solar part of the spectrum is also good, particularly for the brighter clouds, indicating that the properties of the clouds are retrieved well.

“This is encouraging at such an early stage of the mission, giving us confidence in the use of ACM-CAP’s retrieved cloud properties for downstream scientific applications,” Robin says.

There are some differences, however, such as a tendency for the less cloudy parts of the orbit to reflect too little sunlight. “We are currently improving aspects of the ACM-CAP algorithm, taking account of information provided by these radiation comparisons in a range of conditions,” Robin explains.

Comparison of upward radiation measured directly by EarthCARE’s broadband radiometer (with the grey bands indicating the current uncertainty in the calibration) and computed from the retrieved cloud profiles, for the entire section of the previous figure.

Evaluating weather models

To illustrate the power of EarthCARE for evaluating weather models, we have compared the retrievals to the values predicted by the operational ECMWF forecast at a grid spacing of 9 km (the control ensemble member), 14 hours into the forecast.

The figure below shows the water contents, rain and snow rates, and radiative heating rates from the model. Comparing to the retrievals in the earlier figure, we see that in this case the model predicts the rain cloud over Italy at 45°N well, but in parts of the scene it appears to predict clouds too frequently, and the large thunderstorm at around 11°N has been misplaced.

We also see a tendency for the stratocumulus cloud on the right of the figure to be raining too frequently, a problem that has been identified previously in several global models, including in ECMWF's.

“With the Doppler capability of EarthCARE, we can now infer the size of the raindrops and thereby provide crucial new information to improve the representation of precipitation processes in models,” Robin says.

ECMWF 14-hour forecast, initialised at 00 UTC on 18 September 2024, of water content (cloud and precipitation), precipitation rate and radiative heating rates beneath EarthCARE, for comparison with the EarthCARE estimates.

“Huge potential”

Robin is upbeat about the application of EarthCARE data to weather and climate models.

“It is only nine months since EarthCARE was launched, but already from these preliminary results we can see the huge potential of the new measurements for improving the representation of clouds and aerosols in models and how they interact with solar and thermal-infrared radiation,” he says.

Through the Destination Earth initiative, ECMWF is pioneering the use of kilometre-scale global modelling to help tackle complex environmental challenges. With EarthCARE now providing observations at a commensurate resolution and level of detail, it is well placed to help improve weather forecasts and to answer key questions about the role of clouds and aerosols in climate change.