More than 100 scientists attended the CHE and VERIFY project General Assemblies at ECMWF from 12 to 14 March. The speakers included Oksana Tarasova, Chief of the World Meteorological Organization’s Atmospheric Environment Research Division, shown here during a Q&A session.

An ambitious European project to build an operational global carbon dioxide (CO2) monitoring and verification support capability aims to deliver an early prototype in 2021 and a full prototype in 2023, project members meeting at ECMWF for their second General Assembly from 12 to 14 March 2019 heard.

The future CO2 monitoring and verification support capability is intended to support action on climate change in line with the Paris Agreement.

“Producing an early prototype by 2021 and a full prototype by 2023 is an ambitious but achievable target,” says ECMWF scientist Gianpaolo Balsamo, the coordinator of the EU-funded CO2 Human Emissions (CHE) project in charge of building the system.

The CHE General Assembly was held jointly with the General Assembly of the related VERIFY project, which covers three major greenhouse gases (methane and nitrous oxide as well as CO2) and is more closely focused on Europe.

CHE brings together 22 partner organisations from eight European countries and is coordinated by ECMWF.

Key requirements CHE will have to meet include isolating emissions related to human activities from other sources of CO2 in the atmosphere; monitoring CO2 emissions from local to global scales; and providing uncertainty estimates.

One of the speakers at the CHE-VERIFY General Assemblies was Greet Janssens-Maenhout, the chair of the European Commission’s CO2 Monitoring Task Force.

One of the speakers at the CHE-VERIFY General Assemblies was Greet Janssens-Maenhout, the chair of the European Commission’s CO2 Monitoring Task Force.

“To turn the targets of the Paris Agreement into reality, it will be vital for policy-makers and climate negotiators to have as much information as possible on human-related CO2 emissions in Europe and across the globe, including information on uncertainties,” she says.

“The CHE project is making a vital contribution to this effort.”

Isolating human-related emissions

Europe already has a capacity to monitor global atmospheric composition, including concentrations of CO2, in the form of the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) implemented by ECMWF on behalf of the EU.

However, the Paris Agreement requires countries to account for CO2 emissions and removals specifically related to human activities. The EU has therefore proposed adding a CO2 monitoring and verification support service element to its Copernicus Earth observation programme.

“CHE, which started in October 2017, and a successor project expected to take over from CHE in January 2021 are intended to pave the way for such a service,” Gianpaolo explains.

Bernard Pinty, a senior scientist at the European Commission, emphasised that CHE is not a pure research project but is expected to prepare the ground for an operational service.

The future service will be able to draw on essentially two sources of information: measurements of CO2 concentrations by mean of remote sensing and in-situ networks, and knowledge of emission sources and sinks.

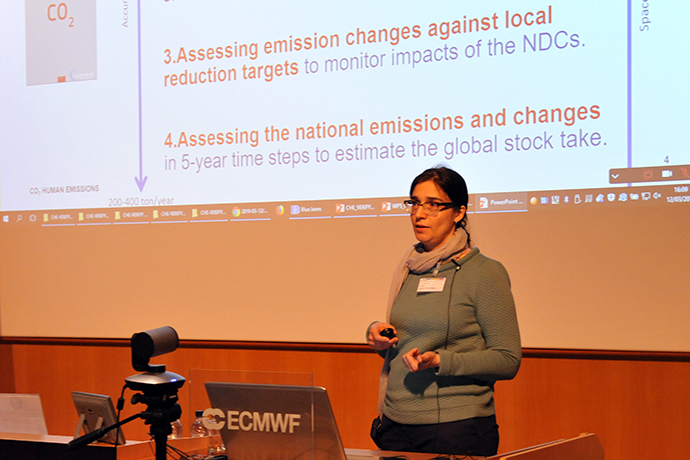

“One of the challenges in interpreting the measurements is to identify the contribution made by human-related activities,” says ECMWF scientist Anna Agustí-Panareda, co-leader of the work package on building the prototype.

“For example, sufficiently high-resolution satellite observations of CO2 plumes together with plumes of co-emitted species such as NO2 can help to identify the contribution made by anthropogenic sources, such as power plants.”

She adds that work on the prototype started in earnest earlier this year after a lot of preliminary work was completed over the preceding 12 months. This has included producing global simulations of atmospheric CO2 using the major global sources of fossil fuel emissions along with biosphere CO2 exchanges and their transport.

ECMWF’s Anna Agustí-Panareda presented progress towards building a CO2 monitoring and verification support prototype.

Multiple scales

The requirements for the prototype system include the ability to assess CO2 emissions at spatial scales ranging from hundreds of metres to the globe, and at temporal scales ranging from hours to years.

The system needs to cover the globe because CO2 fluxes cross national borders. This means that only a global view can provide full information on the source of CO2 concentrations in any particular country.

“The global system will also provide boundary conditions for regional and local monitoring capabilities, which are being developed for Europe as part of the VERIFY and CHE projects,” says Anna. “Bringing all these aspects together in a single system is work in progress.”

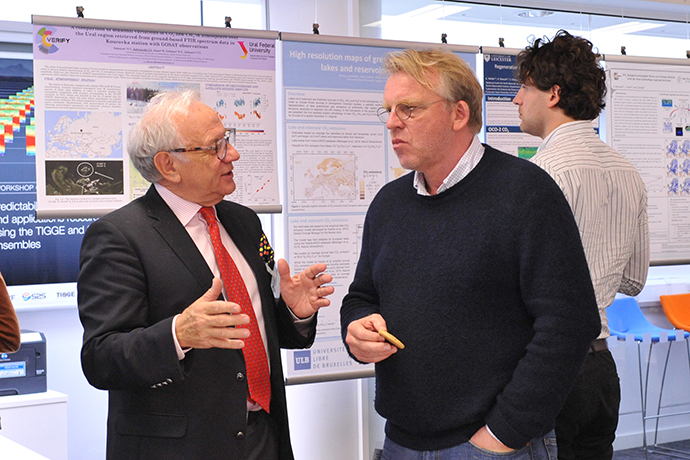

Professor Stephen Briggs (left), who is the project reviewer for CHE, stressed the importance of an ongoing conversation between scientists and policy-makers to make sure that the CO2 monitoring and verification support system meets the needs of its users. He is here talking to Professor Han Dolman, the Chair of the CHE External Advisory Board.

Uncertainty estimates

A key element of the prototype will be the ability to specify the degree of uncertainty associated with CO2 emission estimates.

“There are multiple sources of uncertainty, including in the observations, the modelling of atmospheric transport and our knowledge of emission sources and sinks,” Anna says.

To estimate uncertainties, CHE is pursuing an ensemble approach. In that approach, multiple simulations are run with a range of slightly different initial conditions and slightly perturbed surface fluxes and transport. The resulting spread of results gives an indication of the different sensitivities of the observed CO2 variability and the confidence we can have in the data.

“One of the achievements of the last 12 months is that we have used the capabilities provided by CAMS to produce a long ‘nature run’ high-resolution CO2 simulation as well as CO2 ensemble simulations,” says Gianpaolo.

“One of the achievements of the last 12 months is that we have used the capabilities provided by CAMS to produce a long ‘nature run’ high-resolution CO2 simulation as well as CO2 ensemble simulations,” says Gianpaolo.

“We know the basic requirements for the prototype system and in principle we know how to build it, based on climate and environmental reanalysis experiments and enhanced data assimilation adapted to CO2,” he adds.

“We are thus on track for an early prototype with limited capabilities by 2021, a full prototype by 2023, and an operational system by 2026.”

The CHE project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 776186.